- Home

- Victoria Gosling

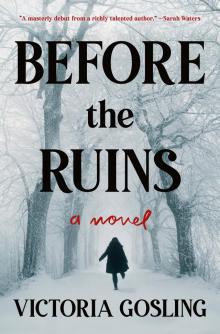

Before the Ruins Page 9

Before the Ruins Read online

Page 9

“Come on. Listen, let’s have a cigarette. Let’s go threes.” Peter started fumbling in his pocket. “There’s something I want to tell you, Andy. It’s bad but it’s good. It’s really bad, but it’s also good. Stay. Don’t go.”

But I did, leaving the pair of them sprawled on the hillside.

By the time I got to the lanes, I was seeing fractals in the clouds, trails when I moved my hands. I got within a couple of hundred yards of the house, and then I climbed over the gate and lay down in the grass at the edge, hidden from the road by the hedgerow.

All the things I wanted to say to my mum were gone. Instead, I watched the barley rippling—the many thousand, thousand assembled ranks of stalks, the lifted ears—and I felt such tenderness for them. The clouds passed. At dusk, a field mouse crept between the rows, such a tiny thing, so busy, seemingly about such important work. I stayed there till it got dark and the ground grew cold.

* * *

Marcus was pissed off I hadn’t spent more time aahing over his ankle and listening to his mum chat on about three-piece suites. He was driving again, but at the manor he wouldn’t play the game, said he had to rest his ankle. I’d hidden the necklace, so I waited with him on the blanket while the others looked.

“What’s up with those two?”

David and Peter were coming round the side of the house, Peter almost on David’s heels, David with his eyes fixed on the ground. Something had happened after I’d left them on Smeathe’s Ridge. Whatever it was, it hadn’t done Peter’s cause any good.

“Dunno.”

“Lovers’ tiff?” There was an edge to Marcus’s voice. I could have placated him by saying something mean in agreement, or putting my hands on him, but I didn’t feel like it. It was a relief when he went back to work.

* * *

We only went out together once, to celebrate our exam results. Mine were solid. Em got an A in art, which was all she cared about. Peter’s were outstanding. Balliol would take him to read law starting October. I’d known it was coming but still had to swallow back the bitterness that flooded my mouth.

“A night on the tiles then?” Em’s mum stuck her head round the bedroom door. She was carrying a plate of cheese on toast, the bread cut into little squares. “To line your stomachs.”

When we were a bit younger, I’d made Em go nicking with me. Never in Marlborough, in Swindon where the shops were bigger. She was surprisingly good at it. Afterward we’d come home and divide the spoils. But we hadn’t been in ages, and I didn’t have anything nice. Em wanted us to wear dresses.

“I haven’t shaved my legs.”

“You can use my dad’s electric razor. I’ll tell him it was Faye.” Faye was her little sister. I tried on all of Em’s dresses, then we hit her mum’s wardrobe. June had been a teenager in the sixties and had the miniskirts to prove it. Em was swishing this way and that in a long paisley number as her mum came up the stairs.

“You put everything back afterward.” She stopped and leaned against the doorframe. “God, I used to be thin. Looks good on you, Em. Very romantic, very Joan Baez. You found anything, Andy?”

I shook my head and she went over and rifled through the rails.

“How about this?” It was violet, very short with a little collar and buttons down the front. “Go on. Try it on. It’ll go perfect with your coloring.”

It wasn’t like anything I usually wore. When I came out the bathroom, a bittersweet look passed over her face.

“I’ll tell you what. The pair of you can borrow them, but only if you let Faye join in for an hour. Slap some makeup on her. Let her show you her dances.”

Before we left, she made us stand together for a photograph. I don’t think I ever saw it. “Such young ladies,” she said and pressed the button.

Lady. Girl. Female. Woman. Each of the words made you feel a bit different, act a bit different even, when it was applied to you. They weren’t the only words for us, of course, only at Em’s house it was possible to forget the other words existed.

* * *

The club played guitar bands, the crowd a mix of grungers, indie kids, Britpoppers, plus a few lost-looking goths and metalers, the remnants of dying species that had failed to evolve.

David wasn’t sure about going.

“I don’t think there will be any wanted posters up,” Em said.

When he was out of earshot Marcus said, “He’s going to have to face the music at some point.”

Later, I wondered whether there hadn’t been someone in the crowd who recognized him. Later, sitting out on the step, waiting for the phone in the telephone box to ring, I would wonder about all kinds of things.

But it was a good night. We did shots. When songs I liked came on, I danced with Em. She was all lit up with booze and mischief. Elbowing our way through the crowd to the toilets, I asked her if she fancied anyone.

“Maybe the one with the Bob Dylan hair.”

So when we went back, I made sure we danced right up by him till he got the message and led her off upstairs to the balcony, but she came back after twenty minutes shaking her head. With boys, it was like she was always comparing them to someone in her head who was better.

When we left, the night was cool after the hot club. We had to wait ages for a minivan taxi. The driver wanted to know why we were getting out in the middle of nowhere.

“My uncle’s got a caravan in the next field.”

After he sped off muttering about pikeys, we waited till the road was empty and climbed over the gate. It was like the first day at the manor, only now it was night, and there were five of us, not four.

In the rose garden, the air was heavy with scent. Em had made colored-paper lanterns and put tea lights inside. She borrowed Marcus’s lighter and managed to set fire to two before he took it from her and did the job himself.

“Why don’t boys dance?” When she was drunk, Em sort of looked out of one eye at you.

“There were plenty dancing.”

“But not you three. Sitting in a corner drinking like old men.” She had the radio in her lap and was sliding the tuner between the stations, slipping between voices and static and crackling music, and I was struck by the otherworldliness of it, as though the stations were not channels but glimpses of other times and places. Suddenly a big band, loud and clear, the kind Mrs. East listened to.

“Andy and Peter can dance,” Em said. “Mrs. East taught them. Show them. Show them how you do it.” And she wouldn’t give up till we did, demonstrating the few steps we knew, gliding up and down the worn stones.

Peter’s touch was light. I fought the urge to hold him, to dig my fingers in. I had that last feeling—last orders, last dance, last summer, last goodbye. The song ended and he let me go like it was the easiest thing in the world.

Em wanted a turn with Peter. Marcus wouldn’t dance with me, wouldn’t let me pull him to his feet, so I asked David. Mrs. East said you could tell what a man was like by dancing with him. David was careful, attuned to everything, pleasant, a quick learner. I saw him cast a glance at Marcus.

“Sure you don’t want to take over?”

So I learned nothing new from dancing with him, unless it was that he didn’t want to be known.

But then, when the music came to an end and we stepped apart, David gave a little exhale when he let go of me. It was the kind you might make after crossing a fast-flowing river via a slippery log. The kind made when you thought at last you were safe.

I heard it and looked up, and saw David realize he’d been found out. But he didn’t look away, and there passed between us something I can only call complicity.

And that was it, I think, the real beginning. That quick out-breath.

CHAPTER 10

SWIPE LEFT

The bus rattled over Vauxhall Bridge, and the Thames—black and gleaming—ran beneath us. So much water, as though somewhere a dam had broken. On my lap I held the telephone box from Peter’s flat in a carrier bag Adewale had given me.

&nb

sp; “It’s mine,” I told him.

“Of course,” he said carefully, and then, “Please will you go now?”

I rather wanted to stay. I had a friend once, an Irishman, Danny, who let me keep him company during his night shifts. He worked security at a shopping center in Stratford, ignoring the flickering feed of empty aisle and car park in favor of books he bought at a market by the river, rubbing his grizzled chin as he tried to teach me chess in the small hours. On Sundays, we walked the city.

“This is where Shakespeare washed his socks.” Or, “Here’s where Jonson killed his man, Andy.”

Danny promising to show me Galway, never showing a sign of wanting to lay a hand on me. There had always been people I wanted to talk to, and people I wanted to touch. On the whole, they had been distinct groups.

On my fingers, I counted the years since I’d been with someone, since I’d properly made an effort to get to know someone. To let someone know me.

At the lights, as though following my thoughts, the bus gave a mortal, shuddering sigh. A taxi would have been quicker, but the bus had been approaching and going in the right direction. Perhaps I’d wanted the company.

All around, heads were bent over phones. At each stop, the eyes flickered up. Danny had been proof that kindness was unavoidable, even if you weren’t looking for it. Still, who knew when one of us would start knifing another or kicking someone down the stairs. A group of beery lads got on and the beauty in the row in front turned toward the window and brought her arm up to shield her face, like a rich man concealing his Rolex within his sleeve.

The cafes were closed now, and the restaurants. A take-away glimmered here and there like hope eternal. In Chelsea, the hospital rooms were darkened, the corridors emitting a weak fluorescent glow. At Sloane Square, a man swung into the seat beside me and opened Tinder, swiping left at each woman’s picture like a person with a nervous tic. What’s wrong with that one, or that one? I wanted to say. You’ll run out if you go on like that. Only he wouldn’t, of course.

I snuck a glance at his face, youngish, not un-handsome, but his brow was furrowed, his cuticles gnawed raw, as though rather than looking for a potential date, he was grimly searching for the perpetrator of a crime that had been committed against him. The thought made me smile, and I turned to the window before he could notice.

I imagined turning back to him and saying, My name’s Andrea! I like working and have no hobbies whatsoever. Bet you can’t guess what’s in the carrier bag. And him drawing down his finger across my face. Left or right?

But after he got off, and for the last leg of the journey home, I took my phone out and quickly found myself doing exactly the same. Looking at the potentials in their sports kit and on beaches, holding puppies, or leaping out of planes. Swipe left. Swipe left. Swipe left.

Because there were so many faces, but none of them—it appeared—ever the face I was looking for.

CHAPTER 11

ENCHANTED PALACE II

We played on through August. The animating spirit that kept the game alive, kept us circling the manor’s grounds, kept up its whisper. Under my feet grass, stone, wood. The birds at dusk. The air so thin, so endless. The light draining, the dew falling. The moon hung over the cornfields and the clouds ran in herds over her face.

David standing beside me on the steps, the shadow of the house cutting across them like a saw blade. Summer was teetering at its height, poised to fall.

Come September I’d work for Darren full-time, do bookkeeping and computer classes in the evenings. Marcus would be Darren’s right hand. Em would do her art foundation. In October, Peter would go to Oxford. David would write the letter, get off the hook. I asked him what he’d do then.

“Why don’t you look at me when you’re talking to me, Andy?”

I repeated the question. “Re-takes then Uni? Travel? A job? Must have lots of chances. Dads of kids you went to posh school with.”

“And you? Going to stay here and become a child bride? Look at me.”

I looked at him. Tiny flecks of amber ringed his pupils. In the right light, scowling, Marcus looked like a Levi’s model, but David, his bones were just right. I liked his skull, and teeth, and hair. His skin. He moved just so. I begrudged him all of it.

“Peter talks a lot of shit sometimes, doesn’t he?” David looked uncertain. He was being serious. “I mean, a pinch of salt. After we took the pills, after you’d gone, he was coming out with all kinds of stuff.”

“What’s he been saying?”

David was good with words, but he didn’t have the right ones now.

The shadow was moving. I could feel it passing over my skin till I was in the plain sun. Even then, a terrible cold wave swept over me, because I suddenly knew what David was getting at. Peter had been talking about me, about my mum, and how awful it had been for me, growing up like that. I could hear it, in my head, all the details, everything that David would be allergic to. He’d probably told him about Joe as well, creating intrigue, his voice full of drama, stringing it out for attention.

Joe could still come back. The feeling, when you opened the front door, when Joe was inside.

“Sent your mum to the shops. Now what you’ve been up to?” Joe was quick on his feet, the chair skidding across the kitchen, blocking the door before you could get back out.

I heard Peter leaning in to whisper the things he thought he knew. A sold-out, hollowed-out feeling.

“Pete wants to suck your cock. He’d tell you black was white if you let him. Are you going to let him?” I smiled, showing my teeth.

“Jealous?”

“Don’t flatter yourself.”

“I wasn’t talking about me. You know, they all do what you want all the time, because if they don’t, you’re a royal pain in the arse. Tiptoeing round you the whole time.”

“And you make people like you so they give you stuff. Or just to win them.” Saying it, I realized it was true. It was why Peter had no power over him, because he’d been so easily won.

David licked his lips, took a quick step forward, and then stopped. From a distance, a shout of triumph. Em’s voice.

“She’s found them again,” I said.

“Fuck.”

“But not the real ones. Not Mortimer’s ones.”

“No. Because I’m going to find those.” David said it lightly, but he meant it. It was what made the game real, what kept it going. David’s belief the diamonds were there and he would find them.

“Not if I do first,” I said.

* * *

In one of the tiny servant bedrooms, I found David peering out a dusty window. I stood in the doorway waiting for him to turn. But he didn’t, even though he must have heard me coming. I didn’t go in. I knew if I went in, something would happen.

I began to know where he was. I was listening for the diamonds, but it was David I heard. During the game, while we played, roaming the house and grounds, it came to be that I could feel where he was.

Even with my eyes closed, my awareness followed him—as he bowled tennis balls at Marcus who sent them flying with an ancient cricket bat, ricocheting off the walls or further smashing what was left of the glass hanging from the frames of the greenhouses. Or as he lay sprawled out at the top of the lawn, his toes pointing down toward the lake, talking to Peter about something or other, his hands occasionally lifting into the air to describe a shape or emphasize a point.

There was a gossamer thread stretching between us. And, as time went on, I began to feel it even when I wasn’t at the manor. At night, for example, lying in my bed, I felt it still, fine as silk.

I’d known something like it once before, but that had been about fear, about knowing where Joe was so I could be as far away as possible.

I tuned in to it, the feeling between me and David. I blocked everything else out. At night, my mother had taken to shouting. Short bursts. Rarely intelligible. Sometimes I woke, sometimes the shouting entered my dreams. Waking, I would not know if it had been

real. Neither awake nor asleep did I reply. I thought it could last forever like that. That I could punish her forever.

* * *

From out of a clear sky the drops came fat and far apart, then faster. Like a silvery applause, then drumming. I was caught out on the path by the lake, the rain cold, roiling the surface. I took off for the house yelling. A deluge. Above the sound of the rain, voices calling from one of the upper windows. Coming up toward the back of the manor, I slowed. What was the point; there was no getting wetter. The water in my shoes, in my ears, blurring vision.

Instinct? Premonition? I ducked left toward the greenhouses. David was sheltering under the bit of glass roof that was still intact.

“Nice and dry, are we?” But he couldn’t hear me over the rain. He said something I couldn’t hear either. The manor was only a looming shape. Water ran in sheets from the glass ceiling, a waterfall around us.

David was still talking, his eyes full of mischief. What was he saying? I took a step closer, and another. I brought my ear to his mouth, but he was only mouthing the words.

His body was warm and dry. I wrapped my chilly arms round him, my wet skin, my soaked T-shirt. I made him shiver. David’s dry cheek pressed against mine. I held David in my arms and he held me back. Wanting meeting wanting. The feeling of touching him this huge relief, like I’d been holding my breath for it.

If there are moments that do great harm—the cruel word said, the fist swung, the bomb detonating in the packed marketplace—could the reverse be true? Not the long slow knitting of bones, or the wound puckering, turning to scab, then scar, but a magic reversal?

They were calling our names from the manor. As I let him go and stepped back, I saw something moving outside, a shape going back around the corner and out of sight.

Before the Ruins

Before the Ruins